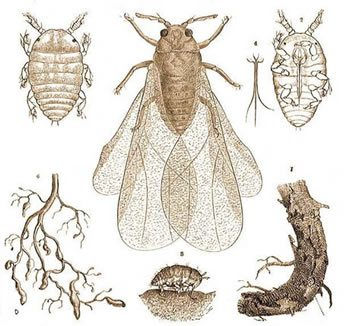

Yes, grapevines have a terrible enemy. Today we will talk about it since many friends have asked me recently if French wines are 'truly' French after the devastation they suffered... Let me explain. In the late 1800s, European wines were almost lost forever. By then many wineries all over Europe were ripped up and burned their family’s ancient vineyards in a desperate attempt to stop the spread of the disease. All because an aphid that came to be known as Phylloxera vastatrix. This microscopic insect, native to the Mississippi Valley of the eastern United States, practically destroyed all the world’s vineyards once freed from its homeland. It changed the wine industry that we know today. In case you wonder how was this possible, well... Phylloxera may have spread through the unintended actions of the man who started Sonoma’s oldest winery, Buena Vista Winery, in 1857: “Count” Agoston Haraszthy. Nobleman, adventurer, traveler, writer, town-builder, and pioneer winemaker in Wisconsin and California, Haraszthy incorporated the Buena Vista Vinicultural Society in 1863, the first large corporation in California (perhaps in the United States) organized for the express purpose of engaging in agriculture. With the support of prominent investors, he greatly expanded his vineyards in Sonoma, making wine which was sold as far away as New York. Nevertheless, his management was considered both visionary and reckless. He borrowed large sums of money to expand the vineyards and cellars. He employed layering as a planting technique which resulted in quicker propagation of vines but also exposed the plants to soil diseases. By the middle of the 1860s, the vines at Buena Vista were growing brown and weak. Haraszthy’s critics believed this was due to his layering. In fact, it was the result of the first infestation of the phylloxera ever known in California. Almost unknown before it made its appearance in Sonoma, the phylloxera spread in subsequent years throughout the California vineyards and even crossed the Atlantic to France, where it caused devastation.

Phylloxera did not suddenly appear in Europe from the ether. Paradoxically, it is understood that the insect was first brought to Europe on specimens of American vines collected by British and European botanists.The interest in American vines had been prompted by the powdery mildew outbreaks in European vineyards in the 1850s. It was hoped the American vines would show more disease resistance. These vines were still thriving, so alarm bells did not ring. Vineyards in Britain were devastated first. Then the problem spread to France and much of Europe. Because phylloxera is native to North America, the native grape species are at least partially resistant. By contrast, the European wine grape Vitis vinifera is very susceptible to the insect. By the 1900s Phylloxera had taken a beyond-imaginable toll: over 70% of the vines in France were dead –the livelihoods of thousands of families were ruined. Then, total wine output in France was less than 28 percent that of 1875. All of a sudden, the world launched into an international wine deficit.

Fighting the blight...

In France, one of the desperate measures of grape growers was to bury a live toad under each vine to draw out the "poison". Areas with soils composed principally of sand or schist were spared, and the spread was slowed in dry climates, but gradually phylloxera spread across the continent. A significant amount of research was devoted to finding a solution to the phylloxera problem, and two major solutions gradually emerged. Vines were saved by the grafting of European plants to resistant rootstalks of vines native to the eastern United States that were immune to grape phylloxera. Hybrids and fumigants have also been used to combat this pest. Today rootstock is still used for much of the wine world and phylloxera is still a danger. The threat is no less in the U.S. In the 1990’s a mutation of Phylloxera called “Biotype B,” was found thriving in a common rootstock. About two thirds of the vineyards in Napa during the 90’s were replanted. Phylloxera has also devastated many ungrafted vineyards in Oregon.

The fight goes on...

Today, the fearsome phylloxera is no longer a threat to Europe as it was in the past thanks to different measures taken in this regard. One of the main ones is the standardized prohibition of the importation of any type of foreign vine, except for research purposes. Therefore, the indiscriminate importation of vines that once caused the arrival of this plague would not be possible today. Another measure in place nowadays is to use the base seedling of the American vine, which, unlike the European-type base, does have the necessary strength to adequately resist the effect of phylloxera on the roots. In fact, nowadays the technique of grafting European cut plants is still used on these bases arrived from America. This would leave the leaves of European cut plants open for this fearsome pest. Fortunately, there are also specific treatments to prevent the development of eggs that female aphids could insert into the leaves. Since they are quite striking, it is not difficult to identify the infected plant, having winter / spring treatments. These are responsible for eliminating those eggs and prevent the proliferation of the pest. An approach that has made phylloxera a bad memory of the past.

So coming back to the question that originated this post... Phylloxera irrevocably changed the world of wine. Did it alter French -or other European- wine itself? It depends on whether you believe that grafted vines produce different-tasting fruit than own-rooted vines. I am a believer that rootstocks -versus own-rooted- show terroir just as well. Yes, I get it, it’s hard not to feel curious about those pre-blight wines but hey, don't let the nostalgia rain too much on your parade.

Santé!

Comments